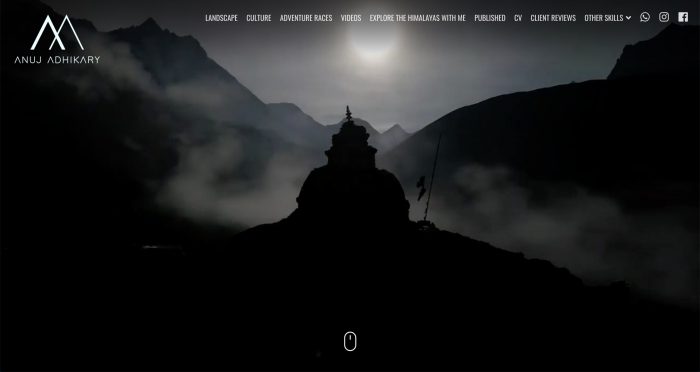

In the Midst of Mountains

Trekking to the mountains is always as challenging as it is beautiful. Whether that switched between idyllic sunshine, relentless rain or a whiteout snowfall, every gruelling step in our trek to the Himalayas was worth it. Trepidations of embarking to high altitudes was thrown into thin air as the night sky glittered with stars, and snow-capped mountains that surrounded us in every direction burst into a majestic sunrise at the Annapurna Base Camp.

Adrift on calm waters of Phewa Lake I massaged my hamstrings in vain attempts to relieve a burning sore. Five hours of involuntary manspreading from Kathmandu to Pokhara in a bus that claimed to have extra legroom (and WiFi) had taken its toll. Yet the discomfort paled before Annapurnas’ grandeur, albeit partially hidden behind scattered clouds. We rejoiced in the morning mist on our last boat ride ensued by a hefty sandwich vital for any trek.

We drove off on jeep from Halan Chowk and after a couple of hours reached Phedi, the starting point of our 9-day trek to Annapurna Base Camp at 4,130m. The gradual uphill climb on stony steps to Dhampus was mere prelude of what awaited. Amidst rice and millet terraces, we slowly made our way up on steps and as the sun scorched, made our way through midhills. With a backpack over 20kgs strapped on my back, the climb would get quite exhausting at times. Layers of clothes got shed by the time we got used to the steps that seemed to know no end. The occasional chautaras as well as Gurung settlements along the wide trail did wonders to help us catch our breath and appreciate the greenery.

Crossing dodgy suspension bridges we reached thick woods and could feel a sense of remoteness of our adventure. Bulls possessive of their femmes were certainly a threat, especially if you had to walk past them while they were mating, which we encountered on more than a few occasions. A brief stop at a shop that sold nak cheese made us smirk on the typo, only to realize that it was not yaks, but their female counterparts naks, that make cheese. As we zeroed in on our first destination Landruk, mountains popped up prominently in a distance just in time to quell complaints about painful legs from uphill walk.

Annapurna’s massifs from the restive Pothana village seemed like from another world altogether. Macchapuchare in its photogenic glory was indeed a treat to the eyes over lunch so delicious that the most insatiable of food critics would be silenced and left salivating for more. After hogging down more servings of dal bhat than we’re proud of, we trailed on, bloated and happy. By this time, the clouds were moving in, which was quite a respite after the dog day afternoon. Weather was in fact perfect as we reached our destination in Landruk. We were settled into our rooms and served hot homemade millet brew called raksi, affectionately called tharra or local. The sleep here was hearty and the sight of the first sight of mountains in the horizon was one to behold.

The jeep tracks from Landruk would dwindle to trails through a forest followed by a gorgeous waterfall. Making our way down towards the fresh white waters of Modi River, we reached a tiny settlement called New Bridge. Distant rolling hills would merge with haze below skies filled with cotton balls of picturesque clouds. It was interesting to note the influx of Nepali tourists, especially youngsters, as we moved up the trails, a few of whom almost tipped us over the cliff by accident when their inebriated selves couldn’t handle the rocky and slippery steps in Jhinu. It then bears pointing out that the prices of beverages (and food) can be pretty steep as it gets more remote. That’s mainly because it has to be carried by porters. We wondered where they got all that booze from. It would take about half an hour’s walk to find that out, as made a pit stop at a small hotel.

A lovely Tamang lady and her differently abled son had championed hospitality to unwitting and exhausted tourists on that climb. Tasty omelettes coupled with fresh pickles from her farm had me licking my fingers. And the liquor she crafted was true to her words: the best and strongest in the Annapurnas. Well, probably. As the only openly drunk raksi-appreciator I took a couple of pegs with the lady. She went on to explain how her last bunch of patrons – half a dozen Nepalese boys – finished a jerry can just a while earlier. No wonder. I would gladly have spent a few hours here, blown away by the jolly hosts, amazing refreshments and equally remarkable views. But we were due for Chhomrong, a ginormous town up a ginormous hill, by dark.

The backbreaking ascent to Chhomrong came without warning. The higher we climbed, the more exhausted we got and better the vantage point. Quite unfortunately, the skies were overcast and mountains up north were shrouded behind gloomy clouds. We conquered the long climb towards dusk and upon arrival at Chhomrong were greeted with chilly drizzles. As everybody prepared to put extra layers of fleece and down, mine went mysteriously missing. Must’ve left it at the omelette place, I thought. So much for merrymaking. The chill in Chhomrong would be nothing compared to the freezing cold in ABC, or so I was told. In a panic-stricken hysteria, I went around early next morning to a million shops trying to find jackets for rent. To no avail. The closest one was one with furry yak wool that made me look like a Siberian hillbilly.

I’d almost given up until I decided to have some coffee in a bakery where croissants looked like swollen boomerangs and the owner’s pretty daughter was basking in the morning sun. I decided to steer clear from the interesting delights, fearing for my tummy. Instead, I settled for some spicy noodles the young lady was having. In fact, after hearing my wardrobe predicament she invited me into her room with a smile. She slowly reached down and pulled out a rusty chest from under her bed. It was filled with medieval-looking clothes, including downjackets left behind by trekkers for her baker father almost two decades ago. Godawful smell and stains from the jackets corroborated her story. Now don’t get me wrong, a good pair to buy would cost upwards of USD 200, and renting would cost USD 10 a day. Instead, she offered it for 50 cents a day. Bingo! I was off with an oversized blue down jacket looking like a clown and smelling like fungus. And with a phone number, might I add.

We really began to feel the altitude Chhomrong onwards as we reached the last few settlements before entering Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP). We arrived at a place aptly called Himalaya whence the mountains towered right above. Soldering on along Modi River raging below and surrounded by rhododendron forests, giant snow-covered peaks followed us. Our ascent seemed endless and just as our legs warmed up and got acquainted to the steps, in rolled ominous black clouds and drenched us in a matter of seconds.

Icefalls and waterfalls were a common site and walking over snow deposits become a breeze as we reached closer to Macchapuchare Base Camp, a station before ABC. The last leg to ABC had our hearts thudding with each heavy step. And if that wasn’t enough, it started snowing hard and mercury dropped further with strong headwinds. Nevermind the mountains ahead, even our steps were far from visible in the inclement weather. Notwithstanding, the eerie feeling of walking on sludge into white Himalayan oblivion was quite thrilling. We were lucky that despite such physical strain in high altitude, our breathing was normal and avoided high altitude sickness as we had taken it slow and steady since day one.

Just as we edged towards ABC on the final path, clouds started dispersing. Almost like the weather gods wanted to save the best for the last, unveiled before our eyes what were phenomenal mountains, some of the highest points on this planet, right ahead, surrounding us in every single direction. Wherever we looked, absolutely stunning sights of elaborate ridges readily took our breaths away and at night when stars lit the peaks, we would stand in awe, sighing at the mountains, ready with a wish, waiting for another meteorite to whiz past millions of stars. More than we could keep count of or even imagine to witness in the nondescript skies of the grind we had escaped.

In bouts of ogling magical landscapes, we forgot that we were soaked wet in the sleet. The heated dining hall came as a warm solace, but not without the price of a singed toe. In burning realization, the heater turned out to be nothing more than a small propane stove under the table, along with smelly boots and socks left to dry. A surprisingly delicious order of pizza was enough to make us ditch the warm room for shivering hours spent outside watching Himalayas in its glory. A peaceful night of sleep was well deserved.

The wake of dawn was no less enchanting. Braving cold chills just before sunrise, we huddled together on the hotel’s tiny patio to watch royal purple glow on Annapurna that gradually turned orange. As the first rays of sun touched the mountain’s eastern flank, a burst of yellow illuminated the summits in a magnificent show of lights and dazzling hues. Annapurna’s furious facade came to life. It was most prominently seen from a short distance away by prayer flags and memorial stones of vanished climbers, spectators in hundreds but dwarfed and humbled by the mountains’ inexplicable might. It is quite fascinating to imagine the monumental feat of conquering mountains, and in that, yourself. Though a daring few have accomplished and lived to tell the tale, memorial stones by the gumba where I stood painted a grim picture. A reminder that mountains are billions of years old, and unlike our transient lives, will be there till eternity. I stood there motionless, numbed, staring into the timeless mountains. Miniscule, as I was and felt, a mere vanishing dot in shadows of imposing rocks. It was a transcendental experience, moving, awe-inspiring and humbling to the knees to say the very least.

My thoughts were cut short when faint sounds coming from far off in the mountains drew my attention. I had lost track of time and the sun now brighter, had started melting previous day’s snow on peaks, causing avalanche high up on the peaks. They looked tiny as they swept their way down, but we knew that if one even half as big got triggered at our spot, a wrath of nature’s hell would be unleashed. The dire prophecy too much to bear led me to seek refuge in a breakfast of pancakes and eggs, which, meanwhile, had gone unregrettably cold. We were thoroughly intrigued and could stay here a whole lot longer, but had a long way to walk back. Snow, foot-deep, got shovelled out at the hotel gate while we packed our bags and prepared to bid the mountains a hesitant goodbye.

Looking back every so often to catch what was now a passing glimpse of the Annapurnas, we retraced our steps. Descents were as deceptively laborious as ascents on the now slippery trail, and especially with heavy rucksacks we were carrying, our knees took an ugly beating. But there was no stopping until walked down to Sinuwa and then Jhunu the next day. Walking back, we couldn’t help but feel proud to have climbed up steps that appeared impossibly steep.

Jhinu was an quite an experience in itself. The hot spring at a hiking distance from the village won’t be obvious. There are no shops by the pool, so our little picnic included snacks and a bottle of local brew. A week of trekking later, relaxing dip in the hot pool served our muscles well. When the heat would become unbearable, it only make sense to take a plunge into the freezing cold waters of Modi River gushing by. It would take sheer luck to avoid tirades (and harassment lawsuits) after nearly barging into ladies’ changing room, thanks to unlabelled doors. The pool was unsurprisingly abuzz with dozens of people. A group of Nepali doctors were on a weekend getaway to the hot spring. As were locals from Ghandruk and Chhomrong on a quick trip to pamper themselves. But mostly it was trekkers like us, trying to unwind and kick back.

Back in our hotel, the owners – a mid-aged down-to-earth couple – partook in an intense and prolonged dohori face-off between our guide and a French-speaking guide. Shortly before midnight as others went to bed, the troupe in dining room, myself a gawky vocal sidekick, was just getting started. After countless rounds of friendly yet intimidating exchanges (and a flurry of noise complaints from sleepy, lacklustre patrons), the party slowly crawled its way to bed well past midnight.

I woke up with a terrible hangover next morning to sensational news that would also explain the toilet filled with holy yuck. Apparently, the French guide in a bid to ease his untimely intoxication (he was with VIP clients) and an unprecedented defeat in dohori (our guide had had prevailed) thought it was a good idea to venture to the hot spring – alone and in pre-dawn pitch darkness. Almost an hour later, an ad hoc SAR team would discover the hapless monsieur a few hundred meters away passed out in cattle cesspool. Embarrassment and dung on his face evident and a foul smell made for the most grotesquely amusing story of this trip. Bad as we felt for him, got a few good laughs out of his drunken stupor.

We reached the spotlessly clean village of Ghandruk in late afternoon, also our final stop of the journey, and explored the quiet, cobbled streets. In the most perfect of Annapurna mornings, familiar sights of mountains, only distant, boasted for a fine setting to recap our trip. We hopped on a bus in Kimche and reached Pokhara in the evening, concluding a trip we’d be bragging about for a long time.

There is no wonder why Annapurna Base Camp is one of the most renowned trekking destinations in the world, one that thousands of trekkers check off from their bucket list every year. For our bunch, it was a dreamy treat to the senses, immersion in a variety of rich cultures and bonding with the wilderness. It was an emotional experience where mystical gompas dotted the snowy abode of mythical yetis, where every exhilarating stride was equal parts tough and rejuvenating, and where showers became luxury and in that cold, barely a priority. Moments spent in the midst of mountains have been etched in our hearts, and they’ve left us with enlivened spirits, tightened glutes, and daydreaming in office cubicle, a longing to return.